Promising to “make two nickels grow where only one grew before,” Ophelia “Birdie” Harwood became mayor of Marble Falls three years before the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote.

Elected in 1917, she was the first female mayor in the state and the first in the United States to be seated by an all-male electorate. Later, in 1936, she became the first woman to serve as a municipal court judge.

Although mayor for only two years, Harwood left a lasting legacy in the river city. According to one of her granddaughters, Nell Harwood Holmes of Yuba City, California, Harwood similarly influenced her large family. Holmes, who died in 2017 at the age of 95, wrote a six-page homage to her grandparents, Dr. and Mrs. George Hill Harwood. Written in 1993, her anecdotes run from nostalgic to celebratory to tragic. A copy of the letter can be found at The Falls on the Colorado Museum in the old granite schoolhouse on Broadway.

As mayor, Harwood delivered on her promise of transparency in government by publishing the city’s budget each year. Her platform included pledges to clean up the town by keeping cattle penned and off the streets and drunks at home or in jail and out of the gutters, according to Holmes.

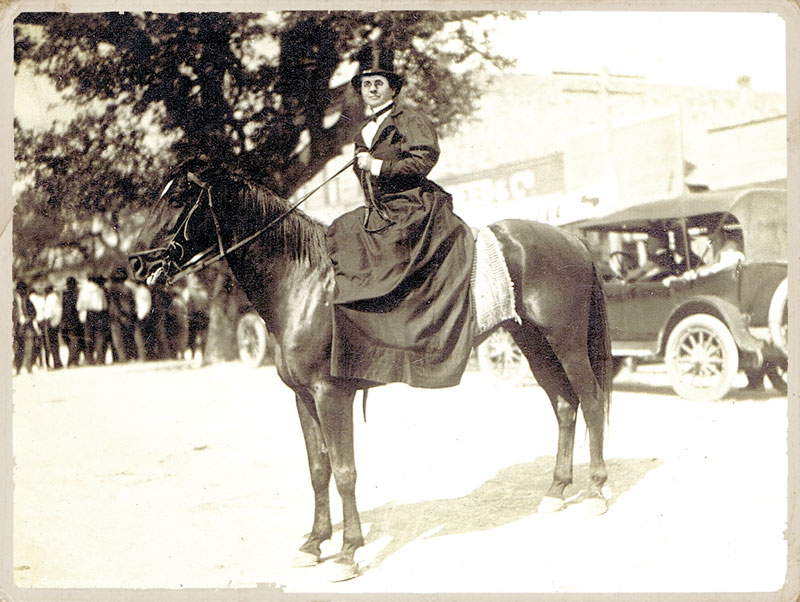

An accomplished equestrian, Harwood claimed to have been riding horses since before she could walk. Named “Birdie” because of her small size when she was born, Harwood, as a child, was given provisions and tied to a horse to roam loose in the outdoors “for her health.”

During the few years granddaughter Holmes lived in Marble Falls, she recalled Harwood piling five of her grandchildren into the one passenger seat available in her Willys-Overland Whippet automobile to drive them to school.

“Every day, I mean, every day, we were five minutes late,” Holmes wrote. “We would spill out when we reached the school, dash over the stile and sprint for the front door.” In all other matters of social life, Grannyma and Granddad were sticklers for propriety. Dr. Harwood “was a very proper Englishman,” according to Holmes. “He had always come to the table to eat in a full suit, including vest,” she recalled.

His table manners “bordered on perfection.”

Grannyma often called her four granddaughters to her bedroom in the mornings for lectures on modesty.

“She had a shocking remonstrance for the girls,” Holmes wrote. “‘Don’t you ever let some man take advantage of you — or your Dad’ll have to kill him!’”

Dr. and Mrs. Harwood’s home was known as Liberty Hall, which still stands at 119 Avenue G, where it now serves as business offices.

Perhaps one of the most famous stories attached to Birdie Harwood and Liberty Hall involves a young teacher who delivered milk to the house as a second job. One day, Harwood presented him with a microscope for his class.

“The young man became the future President of the United States of America — Lyndon Baines Johnson,” Holmes recalled. She was standing in the living room when the transaction took place. “Embarrassingly, I was dressed in shorts.”

Holmes also wrote of the day she, brother Charles, and friend J.B. Cox walked down a steep path to the river. Fascinated by the huge catfish they could see swimming near the surface, Charles leaned over and fell in. Cox saved him by extending a “stout stick” out into the current, which Charles grabbed to be pulled back to shore.

“Grannyma was so shaken when we told her that she told us to find a long switch,” Holmes wrote. “Previously, she had warned us not to go to the river. She had explained how she had combed sand out of the hair of young girls who Dr. Harwood had tried to resuscitate and how Uncle George had dived in the river to bring out drowned persons.”

Those drownings had such an affect on Harwood that, as mayor, she had warning signs erected near the most dangerous areas of the river. This was before the dams were built to form the Highland Lakes.

Tragedy struck the family a number of times. The Harwoods had four sons, all born in Blanco County: Charles Gerald, George C., Francis, and Clarence Adolphus. Francis died at the age of 6 months.

In his later years, Dr. Harwood was hurt while helping rescue several young people from a car crash on the steep hill — now U.S. 281 — south of the river. He never recovered despite the devoted attention of his family, including son George, who spent most of his life at his father’s side. “He and Uncle George were great friends as well as father and son,” Holmes wrote. “How fortunate to have such a great relationship. Uncle George had devoted much of his adult life to driving for Granddad.”

George was devastated by his father’s injury. He was especially disturbed that the family could not afford an expensive treatment he believed would keep his father alive.

“Uncle George took his own life in hopes that proceeds from his (World War I) G.I. insurance would provide the funds (for treatment),” according to Holmes. “Sadly, Dr. Harwood died a few weeks later. Life would never be the same for the doctor’s wife.”

Dr. Harwood died in January 1934. Birdie lived another 20 years, during which she married a childhood sweetheart from Johnson City, Bob Beverly. She was 79 years old at the time. The couple lived in her hometown until her death in 1954 at the age of 82.

“There are many things more to be said and some to be unsaid,” Holmes wrote in conclusion. “But the lives of these exceptional grandparents of mine complemented each other in ways to benefit those whole lives they touched. Dedication is the word their lives personified.”

suzanne@thepicayune.com

Mayor Birdie Harwood: Marble Falls trailblazer

Mayor Ophelia ‘Birdie’ Harwood sits astride a horse on Main Street in downtown Marble Falls. Courtesy photo from The Falls on the Colorado Museum