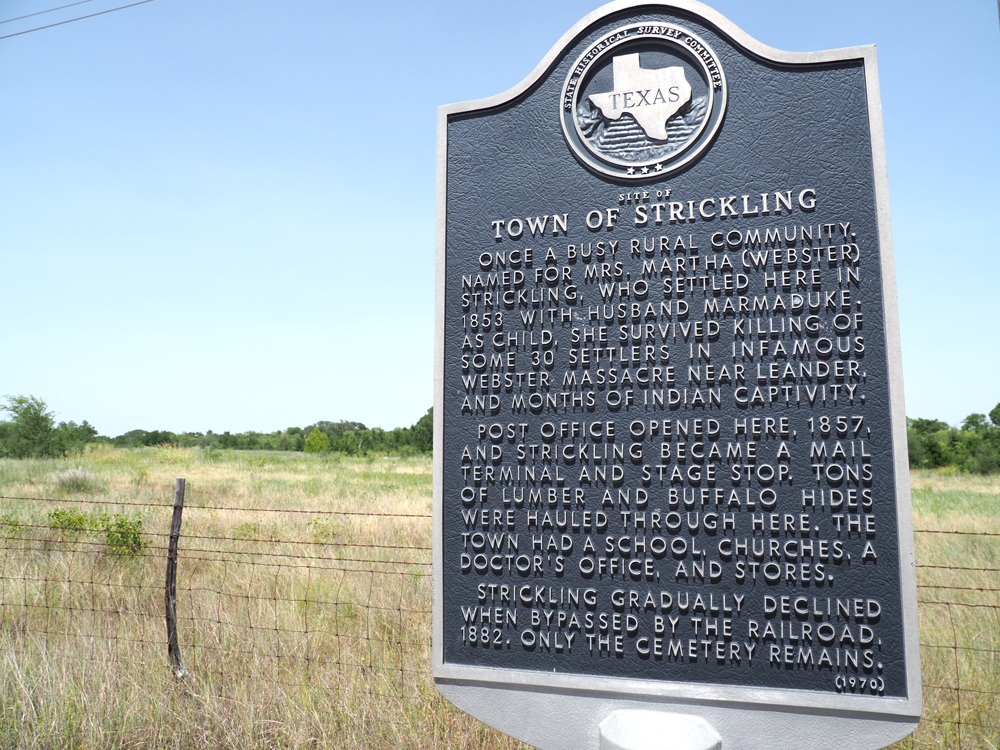

The story of Strickling, a once-bustling town north of Bertram in Burnet County, bares no resemblance to the Strickling of today. If you’re on FM 1174 several miles past Bertram, the only thing that lets you know a town once prospered there is a historical marker on the east side of the road.

The town grew up between Austin and Lampasas in the early to mid-1850s. At its peak, Strickling bustled with a regular stage stop, several churches, a school, a blacksmith’s shop, and businesses.

Yet the town’s story deserves to be retold or, at least, remembered because it might never have existed had it not been for one young woman who survived a brutal Comanche attack followed by captivity and a daring escape led by her mother.

Strickling (sometimes spelled Strickland) was named for its two founders: Martha and Marmaduke Strickling. Though the town took Marmaduke’s last name, it was Martha’s family, the Websters, who actually had claim to the land.

Martha was the daughter of John Webster, the land's original owner. Webster and his family, which included wife Dolly, son Booker, and daughter Martha Virginia, hailed from Clarksburg, Virginia, in what is now West Virginia. He was a successful businessman but also had a restless, adventurous nature. When he learned of the land available in Texas, John Webster moved his family there in 1838, first settling in the Hornsby’s Bend area southeast of Austin.

But Webster had received a grant for “a league of land” on the North San Gabriel River in what is now Burnet County.

In 1839, he decided to once again move his family to claim his grant. He gathered 13 other men to make the journey with them.

This wasn’t Central Texas as we know it today. Austin, at the time, wasn’t a city. It wasn’t even called Austin until the spring or summer of 1839, and it didn’t incorporate until December of that year. What is now the state capital and a thriving metropolis was then a small settlement along the Colorado River.

Webster, his family, the small group of men, and a few wagons headed northwest. They eventually came to a ridge between the north and south branches of the San Gabriel River, but they didn’t find the promised land.

Instead, the party found a large number of Native Americans, reported as Comanche. In later years, Martha Virginia, who was 3 at the time, estimated there were 200-300 Comanche warriors. However many there were, it was too much for the the 14 men, one woman, one boy (11-year-old Booker), and the 3-year-old girl.

The group, believing the Comanches had not seen them, turned back hoping to escape. They pushed on well into the night when, according to one recollection, an axle on a wagon broke while crossing the San Gabriel. The men worked for hours to fix it before continuing their retreat.

Webster also might have believed another part of his company, which had left a day or more after them, would meet up with the smaller group along the way.

The Comanches, however, caught up with them first around sunrise along Brushy Creek just outside of what is today Leander. Webster’s party formed a defensive stand by placing the wagons into a square and took cover inside it.

The Comanches launched an attack, and, according to Martha Virginia, her father and the men put up a tough battle. But more Comanches showed up to bolster their numbers. By mid-morning, the last of the adult men in Webster’s party fell.

A few days after the attack, John Harvey, who was actually part of Webster’s surveying crew but was held up from making the trip with the party, came upon the scene. Harvey raced off to report what had happened to Gen. Edward Burleson, who raised about 60 men in response.

When they arrived at the site of the attack, they were struck by the horror of the carnage: “Only fleshless bones scattered around remained of a brave and courageous band of men,” one report told.

Though the men couldn’t find the remains of Webster’s wife and children, they believed the three shared a similar fate.

Except they hadn’t.

The Comanches had taken Dolly, Booker, and Martha Virginia with them. Accounts differ on where the captives were taken with some saying the San Saba area and others farther southwest past San Antonio.

They were captive, nonetheless.

Dolly Webster, however, wasn’t a woman for captivity. She made three attempts to escape and was caught twice.

The third time, she slipped away with her daughter (her son might have been kept at a different encampment) in the late winter or early spring of 1840. She led her daughter at night for about seven days, ducking out of sight when they spied other Native Americans.

Eventually, the two — with nothing but torn rags for clothes — made it to San Antonio, where they were found. Another account has Dolly Webster escaping by herself after she learned she and other captives weren’t going to be exchanged during a March 1840 agreement. This exchange, or lack of, led to the Council House Fight in San Antonio.

Dolly and her daughter were free from their captives, but Booker would be released later, either six days after his mother’s and sister’s escape or even up to two years.

After their captivity, Dolly and her daughter returned to Virginia, where Dolly died. Booker went on to serve in the Mexican War as part of Col. Jack C. Hays’s First Regiment of Texas Mounted Volunteers. He was mortally wounded and died Jan. 16, 1848, in Mexico City. He was 18.

Martha Virginia Webster returned to Texas to live with relatives. At the age of 17, she married Marmaduke Strickling (she spelled it “Strickland” in many references) and, as the only living heir to John Webster, laid claim to the land in Burnet County. She and her husband moved to the area in 1853, selling some of the property to other settlers. But a part of the land would become the town of Strickling.

The town thrived for many years, even having a doctor’s office, stores, and a post office. But in 1882, when the railroad bypassed the community, Strickling fell into decline as people moved to Bertram, Burnet, and elsewhere.

As for Martha Virginia, she and her husband moved to Lampasas then Gillespie County, where Marmaduke died.

She married Charles Simmons, and they first moved to Oregon before settling in Ferny, California, where she died in 1927.

Now, the historical marker and a cemetery are about all that remain of Strickling.

And you thought it was just a sign on the side of the road.

(EDITOR’S NOTE: As with much history, accounts and details differ depending on the sources. The story of Strickling and Martha Virginia Webster Strickland Simmons draws from several sources, including those that reference Martha’s account.)

daniel@thepicayune.com

On the Road to History: Strickling, Texas

When you’re on FM 1174 north of Bertram, you might notice this Texas Historical Marker that shares a brief story about the town of Strickling. The town, gone now but for the nearby cemetery and this sign, has an interesting history, including a daring escape from the Comanche by a mother and her daughter, who went on to help found Strickling. Staff photo by Daniel Clifton