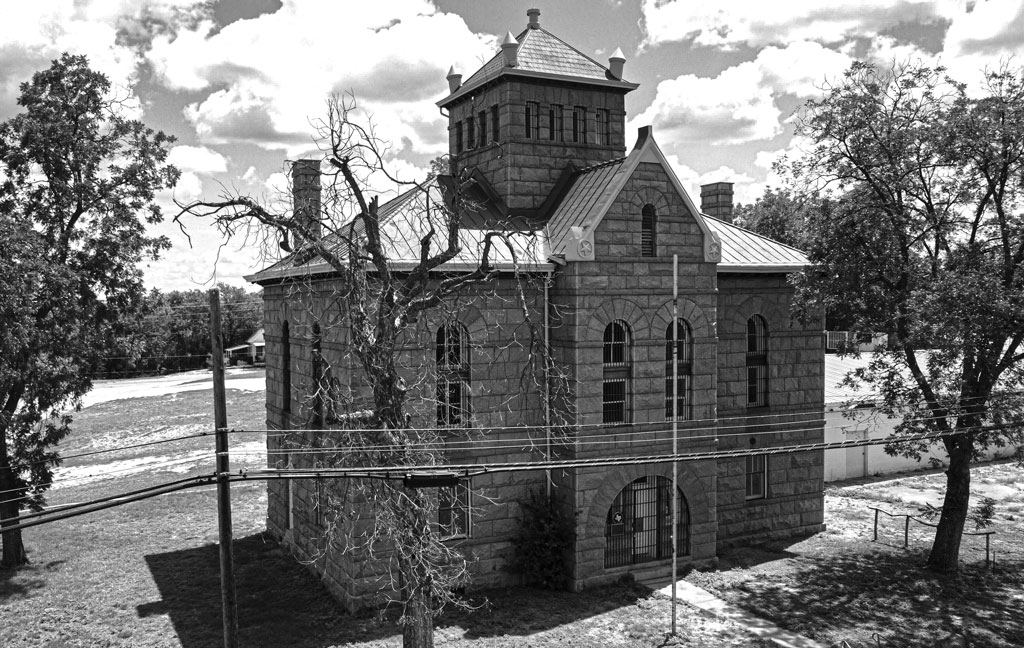

Baby Head Cemetery is one of the few reminders of the once booming Baby Head community, located about 15 miles north of Llano. Staff photo by Daniel Clifton

The men raced toward the large hill, knowing a child’s life lay in the balance. The men, settlers from north of Llano, pursued a group of raiding Indians.

Thought to be Comanche, they had taken the little girl during the raid. Native Americans often kidnapped white children, keeping them as their own and raising them as part of their tribe.

The men rode fast, hoping to rescue the girl.

Up ahead, the Comanche party, some on foot and some on horseback, tried to outdistance the settlers. They climbed a hill north of Llano but realized that, at the pace they were going, they probably wouldn’t escape their pursuers.

Somewhere on the rocky hill among the trees and outcroppings, the Comanche realized the child was holding them back. So, according to oral histories, they did the unthinkable: They murdered the girl and left her head on a pole leaning against a rock for the settlers to find.

Imagine the horror of the men as they climbed that hill and saw the macabre scene.

While not necessarily a ghostly haunt, that hill—referred to as Baby Head Mountain—and the nearby community of Baby Head conjure up the terrifying event from the 1800s that’s part of the Highland Lakes’ haunted past.

But this is just one account of how the Baby Head community, located about 15 miles north of Llano, got its name. Though most of the details are similar, the year and the people involved are a bit different in each telling. In one account, the perpetrators are very different than the ones in the accepted narrative.

Most, if not all, of the accounts behind the name come from oral stories.

According to the historical marker placed at Baby Head Cemetery, the above incident happened in the 1850s, with one account putting it in 1855. And it’s been pretty much accepted for years.

Then, in 1983, John E. Conner’s memoir, “A Great While Ago,” came out. Conner, who was about 98 when he finished his memoirs and spent his boyhood in Llano County, recounted a different take on the Baby Head name genesis.

According to Conner, the incident actually occurred in 1873, and it might have involved the group of Native Americans who fought settlers south of Llano on Packsaddle Mountain.

In his account, Conner said the Indians raided the area and kidnapped Bill Buster’s daughter. They raced off with the child, who—depending on the version—was an infant or as old as 4. The settlers pursued the raiders, but it was a few days later, after possibly being alerted by circling vultures, that they recovered the child’s remains with only her head distinguishable.

Now some could point out that Mr. Conner, who was almost 100 when he penned his memoir, could have been suffering from a faulty memory. His description of the location was also questioned because it was a bit farther away from what became Baby Head community.

Still, longtime Llano County historian Alline Elliott corroborated Conner’s version in published reports many decades ago. Her husband, Sydney, was 17 years old in 1873 and working on a Llano County ranch, and his stories of that incident fall in line with Conner’s.

Elliott pointed out that the community in question didn’t become known as Baby Head until the 1870s. She even identified the child as Mary Elizabeth in one published story.

Considering the horrible scene the pursuers uncovered in the 1850s, is it possible they did not refer to the area and the mountain as Baby Head so soon after the painful event because it would have been a grisly reminder? Could the name have only gained traction years later when people started describing the nearby mountain as “where the baby’s head” was found?

Or maybe these were two entirely different incidents. In the history of settlers’ westward expansion into native country, both sides committed atrocities against the other—including the killing of children.

Which brings us to another possible scenario in which the killers weren’t Native Americans at all.

But first, here’s some things we do know.

The Baby Head community prospered in the late 1870s. In 1879, a post office was established as settlers, farmers, and business owners pressed into the area. By the 1900s, Baby Head was a thriving community with a general store, a blacksmith’s shop, a cotton gin, churches, and even a school.

And it did go by Baby Head, though many people in the area spelled it as “Babyhead.”

However, like many small towns that dotted the Texas landscape in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Baby Head succumbed to progress. With its proximity to Llano, a larger town to the south, and improvements in transportation, people started moving away. In 1918, the post office closed.

The cotton gin hung on until sometime in the 1920s as land use shifted from farming and cotton to predominantly ranching. The store closed around 1940 with the school shuttering in 1944 as students began attending class in Llano.

Today, a few ranches and homes can be found around the area, but the main reminder of the community is the cemetery, which still bears the name, and, of course, nearby Baby Head Mountain.

But back to the big mystery.

In the 1990s, Llano County historian Dale Fry came across another story of how the community got its name.

A Llano resident recounted a tale to Fry that was originally passed down by the man’s great-great grandfather, M.L. Webster of Cherokee. According to this version, the child’s death happened around 1868.

The killers, according to Webster, who passed it down to his son, who then told it to Fry’s source, were not Native Americans at all but “wealthy and powerful” local ranchers. The story goes that the men approached Webster, who was well thought of in the Cherokee community just north of what became the Baby Head community, about a plan to murder a homesteading family.

The idea, as the story goes, was that the men would kill the family to get the attention of the U.S. government in hopes of having a cavalry unit or other military protection assigned to the area. The government had already dismantled a number of forts in Texas because they felt Native American threats had declined to the point that locals could handle them. The men allegedly involved in the plot believed Indian attacks were still a problem and warranted military intervention.

Another reason, and probably just as interesting, is the ranchers believed killing the family and laying the blame on Native Americans would prevent more homesteaders from flocking to the area and laying claim to good ranching land.

If this version is true, then the men only killed the child.

Webster shared the story after learning of the girl’s death a few years later. He was never involved in the plot or the murder, according to Fry’s source.

As for the results, the U.S. government didn’t send troops and the killing didn’t seem to curb settlers’ interest in the area. The only thing that happened is the men involved managed to keep it covered up. Some think that might have been due to their power and influence.

The child is the only constant in the stories surrounding Baby Head. And any connection between her and the cemetery are simply location because she’s likely not buried there. The oldest documented grave in the cemetery is that of another child, who died in 1884.

While the mystery around Baby Head and who’s responsible for the girl’s death remains, one thing is true: A young child suffered a needless death and never got the opportunity to see her life fulfilled.