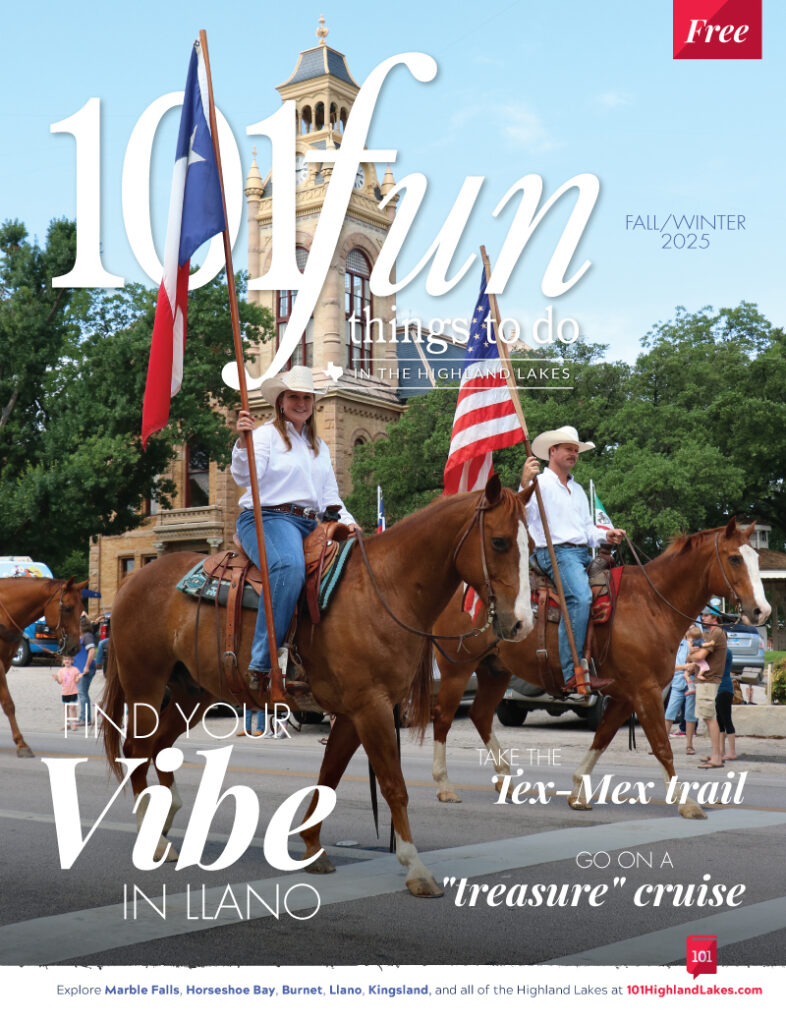

A five-lined skink. Skinks typically lose their bright colors as they mature. iStock images

Don’t blink or you’ll miss this reclusive insect eater and friend to gardens everywhere

Skinks sound like a character straight out of a Dr. Seuss book — they even act and look like one. If you ever get a chance to see one of these shy, well-hidden lizards, look for legs (or not). Many of their streamlined, snake-like bodies are legless. Even those with four legs slither through the soil like their reptilian cousins.

Texas has eight varieties of skinks:

- five-lined

- four-lined

- many-lined

- little brown

- broadhead

- Southern coal

- Great Plains

- prairie

They range in length from 4-8 inches and are covered with shiny scales.

A gardener’s friend, skinks eat pests such as snails, slugs, grasshoppers, crickets, moths, cockroaches, and, on occasion, small mice.

Predators that dine on skinks include birds, foxes, raccoons, skunks, opossums, snakes, and even cats and dogs. Skinks, like other lizards, will drop their tail to escape a predator. The wriggling tail separates from the body in an attempt to distract the attacker, allowing the skink to make a quick escape. The tail soon grows back, however, hopefully before the next predator.

Skinks might try to bite if threatened but not to worry: One thing they do not have in common with some snakes is they are not venomous. In fact, the bite is too light to break human skin.

As with most lizards, skinks breed in the warmer months. About half of the varieties of skinks lays eggs, while the other half gives birth to live offspring.

Female egg-laying skinks lay anywhere from 4-12 soft, rubbery eggs in a nest of loose, moist soil under rocks, logs, or other debris. Sometimes, several females lay eggs in one communal nest, taking turns guarding the eggs until they hatch about two months later. Young skinks are on their own within two days of hatching.

Although they are common in the Highland Lakes, skinks are so reclusive that many people are not familiar with them. If you do see one, leave it alone. It provides natural pest control around your plants.

THE SKINNY ON SKINKS

- They rarely climb, preferring life on the ground.

- Juvenile skinks are more brightly colored.

- Colors change or fade as they mature.

- Males will engage in fierce battle with each other for territory and females.

- Skinks enter a state of inactivity, or torpor, called brumation during the winter.

CREATE A SKINK-FRIENDLY ENVIRONMENT

- Leave plenty of loose soil or leaf mulch around for nests and hiding places.

- Place a small stick in a shallow water dish so skinks can get out after a drink.

- Avoid using pesticides and keep pets out of the garden.