NULL

LLANO — Bill Moss charged through the brush, urging his Missouri mule on for everything it had. He pulled the mule to a stop, jumped off with a gun in his hand and found himself among a band of Indians.

Moss fired.

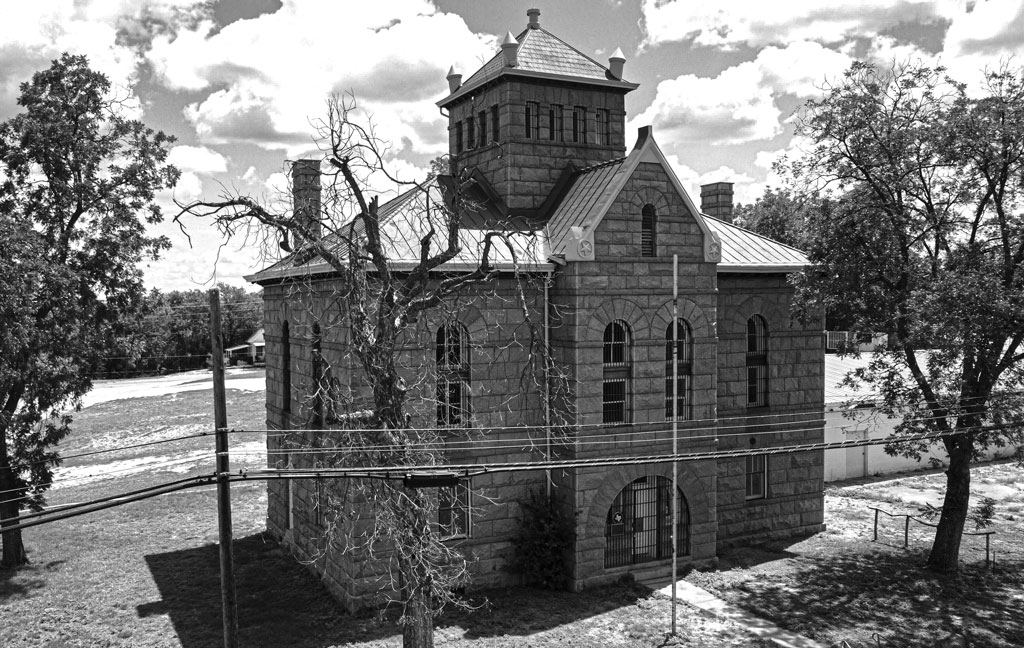

Moss, a local settler who was riding the mule after Indians stole his horse and several others, was joined in the fracas by fellow rancher E.D. Harrington. The two led the charge with six more settlers coming up behind them.[image id="17824" title="Packsaddle Mountain in Llano County"] Llano County’s Packsaddle Mountain today. It is located south of Llano and northwest of the juncture of the Llano and Colorado rivers. Photo by Clay Dupree

But the Indians, though taken by surprise at the sight of a settler charging into the midst riding a mule, quickly opened with a furious volley of bullets and arrows. One of the rounds found its mark in Moss’ chest and he went down.

Harrington and the six other settlers, led by Bill’s brother Jim Moss, returned fire. But if they were hoping for a quick rout, the men instead found themselves in a battle for their lives on Packsaddle Mountain just after noon Aug. 4, 1873.

It would go down as the last fight between local Llano County settlers and Native Americans. While it might not compare to larger battles, for these eight men — Jim Moss, Steve Moss, Bill Moss, E.D. Harrington, Arch Martin, Eli Loyd, Robert Brown and Pink Aires, who was visiting from out east — there was a good chance they wouldn’t come down from Packsaddle Mountain alive.

Though conflicts between settlers and Indians had become much less frequent in the 1870s in this part of Llano County, they still happened. Typically, it was a party of raiders looking to steal horses or livestock. A few days before on Packsaddle Mountain, several horses went missing from area ranches.

On Aug. 3, a cow bearing an arrow in its side ambled back to one of the ranches, confirming the presence of Indians. Jim Moss quickly gathered up the group of men and headed out early Aug. 4 in pursuit of the Indians.

Bill Moss, by far the best tracker of the bunch, led the way. The trail eventually took the men to Packsaddle Mountain, located south of Llano and northwest of the juncture of what are now the Llano and Colorado rivers.

The eight men were making their way up the southeast side of the mountain when they spied an Indian perched on a rock outcropping. The Indian was apparently a lookout, but he was either asleep or whittling away because he didn’t notice the eight men approaching. When they were in range, the settlers took a shot at the lookout, but missed.[image id="17825" title="Battle of Packsaddle Mountain"] A marker stands as a reminder of a battle between settlers and Native Americans on Packsaddle Mountain on Aug. 4, 1873. Staff photo by Daniel Clifton

The Indian let out a yell, alerting the others something was wrong, and raced off.

Bill Moss, on his mule, and Harrington charged in first with the other six close on their heels.

The settlers managed to put themselves between the Indians and their horses, cutting off a quick escape.

“They fought like demons to dislodge us,” Harrington later recounted.

Brown let out a mix of what’s best described as a yell and a yodel that either scared the Indians or confused them during the initial attack.

“The Indians charged us so furiously and repeatedly that within a very short time, three of our men were wounded and out of the fight,” Harrington recalled about the battle many years later.

The Indians pulled back after the first assault, but not without doing a good bit of damage. Bill Moss laid on the ground with a bullet wound to his chest. Martin was hurt and “suffering greatly” as was Lloyd.

Steve Moss and Harrington gathered up Bill Moss and placed him behind a tree. Harrington realized the Indians were working around them in a circle, so he took off to lead them away from the wounded Moss.

Jim Moss, who was leading the pursuit, ordered the men over a nearby bluff, but as they attempted the move, the Indians unloaded a ferocious volley of fire. Seeing the warriors had cut them off, Jim Moss ordered the men back to form a line.

The Indians, led by a brave chief the settlers came to respect for his courage and tenacity during the battle, charged several times. Each time, the settlers held them off. With larger numbers against them, the ranchers knew it wouldn’t last. But with each charging wave, the settlers inflicted damage of their own against the Indians.

Finally, the chief mustered up one more charge. He raced forward, looking to grab some of the horses the ranchers had cut him and his party off from. Harrington said years later that as the chief emerged from cover, the settlers all saw him and took aim.

Accounts differ if it was two bullets or four that killed the chief, but after the lead rounds hit him in the chest, the man struggled on for several yards despite his mortal wounds before falling.

The eight settlers braced for one final assault, knowing this could be it, but it never came. Instead, the remaining band of Indians slipped away.

The ranchers let them go and turned their attention to their wounded. Harrington gathered up the Indian horses and stolen mounts — adding up to about 30. They then secured the wounded and headed for the nearest ranch, the Duncans’ place. Once there, Harrington raced off for Llano and returned at about 9:30 p.m. that same day with a doctor.

Though none of the settlers died from their wounds, the doctor couldn’t remove the bullet from Bill Moss’ chest. Instead, the bullet plagued the Texan for the rest of his life.

Aires, who was visiting from Virginia or maybe one of the Carolinas when he got caught up in the pursuit, left Texas after the battle and, as far as anyone knows, never returned to the Lone Star State. Most of the men were in their 20s, though Jim Moss was 30 at the time of the battle.

Reports differ regarding whether the band of Indians were Comanche or Apache, though there’s no definite answer. One of the saddles found by the settlers had ties to Tucson, Arizona, leading them to suspect the Indians were Apaches.

Harrington would outlive all the men, even returning from Arizona, where he settled in his elder years to see the state of Texas place a marker on Packsaddle Mountain commemorating the battle. The state added another marker along Texas 71 that gives a very short description of the battle, but more in-depth information is available at the Llano County Public Library in Llano.

The Aug. 4, 1873, fight lasted only about an hour, but it would mark a big part of local history. And had it not been for the Indian lookout being asleep, the ending might have been a bit different.

daniel@thepicayune.com